This week for movie club Mikel picked an awe-inspiring anthology from Japan: Memories (1995). Clocking in at just under two hours, Memories is an animated collection of manga short stories written by Katsuhiro Otomo, creator of Akira and Steamboy. The film is divided into three segments, each directed by a different person: Magnetic Rose directed by Koji Morimoto, Stink Bomb directed by Tensai Okamura, and Cannon Fodder directed by Katsuhiro Otomo himself. Satoshi Kon, a venerable director in his own right, wrote the screenplay adaptation for Magnetic Rose, which may have contributed to its haunting voice, but I’m getting ahead of myself. Read on to see my thoughts on Memories.

The following contains spoilers for Memories (1995)

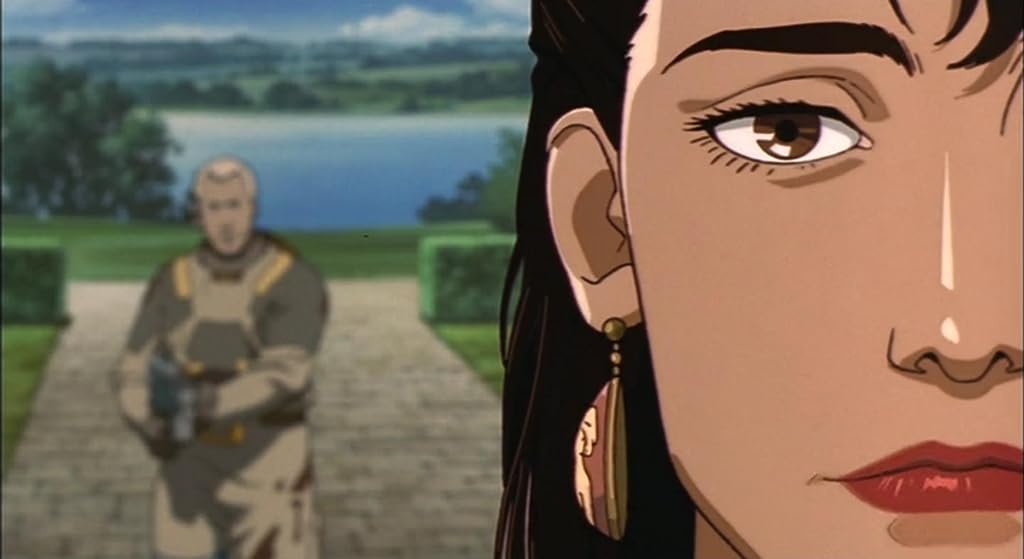

The first segment, Magnetic Rose, tells the story of a crew of salvagers aboard a spaceship, the Corona, who respond to a distress signal. The eclectic crew we follow is headed by Heintz and Miguel, the “away team” who board and explore the giant space station that the signal originates from. Immediately it’s clear that this is no ordinary space station, as the intrepid explorers discover an opulent European ballroom at the interior, giving the structure a feeling more akin to a haunted mansion than a satellite. As Heintz and Miguel explore, they find that many of the space station’s automated systems are still online, preparing food for seemingly no one, and projecting holograms of a famous opera singer named Eva. Bit by bit, the explorers discover that Eva had a tragic lot in life; she lost her ability to sing, ending her career, and just before she was married to the love of her life, he suddenly died. Miguel in particular seems susceptible to the projected memory holograms, and he finds himself being seduced by Eva, filled with a desire to become her late husband, Carlo, and live with her forever. Heintz sees the deceptions for what they are, but is still made to hesitate when he begins to relive the painful memories of losing his family, or perhaps they were simply terrifying images that were projected onto him. In either case, Heintz realizes what they are dealing with: the AI of a derelict ship running amok. The projection of Eva appears, holding a facsimile of Heintz’s daughter, informing him that he will never leave. Heintz shoots at the hologram, and then the massive computer he sees above them, damaging the system and causing the AI to malfunction. Meanwhile, the crew aboard the Corona find their ship being pulled into a massive magnetic field. They recognize the graveyard of ships surrounding the space station must have suffered the same fate, and attempt to break free of the magnetic pull. They fire an energy weapon into the space station, which pierces its hull, breaking the airlock and sucking Heintz into the vacuum of space before the Corona is crushed by the magnetic force, and smears across the floating wreckage in a rose-shaped pattern. Eva is singing over all of this, and it’s incredibly haunting. The segment ends revealing Eva, the real Eva, a mummified husk who died peacefully in her room at the center of the space station, and a glimpse of Miguel, still enthralled by Eva’s memories, and completely seduced into believing he is Carlo. Outside, drifting through space, Heintz awakens, and sees the titular magnetic rose, in all its terrible beauty.

Magnetic Rose was directed by Koji Morimoto, an animator who worked on films such as Robot Carnival (1987), Akira (1988), and Mind Game (2004). He is most widely known as a freelance animator, but around this point in his career he began to transition towards directing. This segment is positively breathtaking. The aesthetics of the dilapidated European ballrooms combined with the spellbinding music composed by Yoko Kanno (composer for the music used in Cowboy Bebop, Escaflowne, and too many other projects to list here) creates an atmosphere that just exudes horror. As mentioned above, this segment’s screenplay was written by Satoshi Kon (Paprika (2006)), whose fingerprints mark the project with heart pounding human interactions that make the cast easy to empathize with. This is actually only Kon’s third time writing for the screen, his first being an adaptation of his own manga, World Apartment Horror (1991), and three episodes of the 1993 OVA of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. Kon is seen as a somewhat tragic figure in the anime world, as most of his works are considered masterpieces, but he sadly died of health complications fairly early into his career, but his work still resonates strongly today. While watching this section, the visuals alone sparked a conversation in our watch party about whether Christopher Nolan (Inception (2010)) could have been inspired by some of the visuals and storytelling in this piece. Being a short story, we don’t get a lot of establishing information about the world, but it almost serves to further isolate the audience into the confines of Eva’s derelict space station. Like a ghost, Eva pulls our perspective characters into her memories of the past, disorienting us and entrapping them in a labyrinth we can’t escape from. It’s really effective.

The second section is entitled Stink Bomb, and it follows the story of lab technician Nobuo Tanaka, who after mistaking an experimental bio weapon for cold medicine begins to produce a toxic and smelly nerve gas from his body that renders anyone who comes within a certain proximity of him unconscious. Unfortunately for everyone, Nobuo is a bit of an airhead; he takes a nap after the initial dose, so he isn’t awake to hear the scientists around him panic, and when he wakes he is almost obstinate in his quest to find other people and get help. He reports the incident, and is instructed to deliver the experimental drug to Tokyo, as the directors don’t realize that Nobuo himself is the epicenter of the disaster. As he makes his way towards Tokyo, the smell he emits becomes more foul. He calls for an ambulance, but the drivers crash when they get too close to him, birds drop out of the sky as he goes outside, the gas seems to harm everything except plants and flowers, which are suddenly flowering in abundance around him. Eventually, the Japanese government figures out what is happening, and tries to reason with Nobuo, even going so far as to fly his grandmother out in a helicopter to try to direct him away from Tokyo. Nobuo is, unfortunately either clueless or unreceptive, continuing his dread march towards the city and bringing the noxious fumes with him. As one might expect, in a utilitarian move, the government officials become scared and frustrated, electing to kill Nobuo rather than treat him. This instigates a lengthy sequence in which the Japan Self Defense Forces try to stop Nobuo, unleashing the full yield of their combined forces. Snipers fire from distant positions before the smell becomes too much to bear, tanks blow up bridges Nobuo tries to cross, and fighter jets scramble to bombard the man in a volley of missiles. Eventually, the JSDF runs out of steam, and the big guns have to be called in: they open the lines for international support, and the U.S. military, who have been monitoring the situation take over the operation, and aim to capture Nobuo alive; they’re invested in the experimental bio weapon, after all. The U.S. then sends in a strike team outfitted in cutting edge space suit technology to extract Nobuo. All this time, the green gloom emitting from Nobuo seems to have gotten worse. Electricity crackles in the air around him, shutting down electronics and machinery, and the sphere of death around him grows larger. In the final scene, a faceless American space suit delivers the experimental weapon to the Japanese government’s headquarters. The team cheers for the mysterious courier before he reveals his face: it’s Nobuo, still unaware of the noxious fumes he emits that are being trapped inside the suit. Then he exits the suit, and gas fills the room, presumably incapacitating everyone.

If it wasn’t clear from the description, Stink Bomb is a huge tonal shift from Magnetic Rose. Where Magnetic Rose is dark and fatalistic, Stink Bomb is irreverent and loud. It was difficult to shift gears so quickly, which clouded my view of Stink Bomb to be equally dark; I became frustrated with Nobuo’s absent-mindedness in the face of a biological disaster, and it wasn’t until the segment was almost over that I warmed up to the idea that this was a dark comedy. There were also discussions within our watch party of how this piece ties in with the theme of memories; where Magnetic Rose is fairly obvious in its statement that memories can entrap us in a bittersweet dream, Stink Bomb doesn’t really have anything to say on the subject. This week’s picker, Mikel, observed that while watching Stink Bomb, he couldn’t help but reflect on Magnetic Rose, a segment he enjoyed a bit more, going as far as to say that he almost felt nostalgic for the first segment, really capturing the feeling that Eva was praying on, and experiencing how memories can often smell sweeter than our present circumstances. But I digress…

Stink Bomb was directed by Tensai Okamura, a notable key animator and storyboard artist who worked on anime projects like Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), Cowboy Bebop (1998), and Wolf’s Rain (2003). His portfolio is full of recognizable anime series; he originally worked at Madhouse before leaving to become a freelance artist. Despite that, Stink Bomb is actually his debut as a director. Looking at his history, one can see what influenced the exhilarating military vehicle shots, and the almost comical amount of destruction that takes place in this story. This segment also features music composed by Jun Miyake, a jazz musician who is better known for working on live action projects, particularly foreign films, although one of his pieces appears in the soundtrack of Eat, Pray, Love (2010). Miyake’s work here was the star for me; this soundtrack slapped, and I look forward to adding it to my regular music mix.

The third and final segment is entitled Cannon Fodder, and it depicts a totalitarian society that is perpetually at war. Every facet of society has been fitted to further the war machine; from a young age, we see children are educated for the express purpose of growing up to fire massive cannons, which almost every house and building are equipped with. The city is surrounded by obscuring clouds of smoke, there is never any visual confirmation of an enemy, or what these massive artillery weapons are firing upon. This section doesn’t depict a story so much as it explores a setting, panning through various levels of society, all of which serve the purpose of training, manufacturing, and firing the colossal weapons.

Perhaps what was most chilling to me was the depiction of the boy character’s dreams: although he is behind in school and has all the features of a typical daydreaming schoolboy, his only dream is to be the man who pushes the button that fires the largest cannon on the moving city; even in his imagination, in his most carefree aspirations, he is obsessed with the war machine and has no concept of anything beyond it. I also found it interesting to see that despite how severe and regimented this world is, we still see scenes of peace, like the mother talking with other women on the assembly line; this isn’t a world devoid of joy, it’s a world devoid of memory. All the citizens are stripped down to their most essential roles, but they still find momentary peace. However, they’ve lost sight of where they came from, what they’re fighting for, and what, if anything, comes next. All they know for certain is that the war will continue.

Cannon Fodder was directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, who is better known for his manga and live action filmmaking; he doesn’t often step into the role of animation director. Since he is the writer of all these stories, it’s interesting to see him stretch his legs. This segment takes on a totally different art style, one evoking more of a storybook. It was interesting to also see his use of the Nazi “SS” symbol in the writing of the people in this world; their letters are stylized English, but the symbol itself feels like an explicit connection to the German war machine of WW2 (especially its use in the word “poisson”). It was a gripping short, albeit somewhat slow and difficult to understand at times.

Overall, Memories was an incredible ride. I feel the stories were arranged with purpose, Magnetic Rose is the most captivating and exhausting short, so it’s served first, while the following two offer shorter stories that are somewhat easier to digest. The stories don’t feel connected, but I do wonder how they were selected for this collection; although they aren’t explicitly tied together, the different segments contrast well and lend themselves to discussion. My favorite of the three was Magnetic Rose, but all three segments are interesting for different reasons. I’d absolutely recommend these to anyone and everyone who enjoys the work of Katsuhiro Otomo and Satoshi Kon. When people try to express that anime is more than children’s media, they’re talking about works like this.