The following review contains descriptions of sexual content.

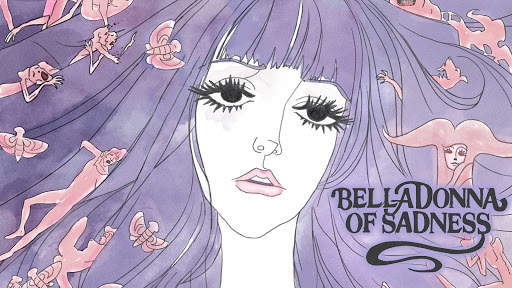

I love suggesting animated movies when it’s my turn to pick for Movie Club. I am seldom more captivated by film than I am when watching animation, and I love learning the stories about the production that goes into making an animated feature. I had heard about this anime classic years ago, but never had an opportunity to watch it, in part because of the film’s graphic content; the film garnered an X rating because of its sexual content. That said, the watch party was excited when I mentioned the flick, and I couldn’t turn down the opportunity to watch it in a group. Read on to see my thoughts on Eiichi Yamamoto’s masterpiece, Belladonna of Sadness (1973).

The following contains spoilers for Belladonna of Sadness (1973)

If Yamamoto’s name seems familiar, it’s because he’s an anime legend. Yamamoto wrote for and directed TV anime adaptations of Osamu Tezuka’s works Astro Boy (1964) and Kimba the White Lion (1966). He also worked with anime giant Leiji Matsumoto writing and directing the iconic series Space Battleship Yamato (1974-1975). If you’re an anime fan, even if you haven’t seen these works, you’ve likely heard of them. Yamamoto played a pivotal role in shaping anime’s history, and inspired many of the great artists whose work we still see in animation today. Those familiar with Yamamoto will know that he directed a trilogy of adult-oriented films conceived by Tezuka known as Animerama in the late sixties and early seventies. These films, A Thousand and One Nights (1969), Cleopatra (1970), and today’s pick, Belladonna of Sadness, employ a blend of traditional animation techniques as well as limited animation and still paintings inspired by the methods of American animation studio UPA and Japanese cartoonist Yoji Kuri. Although Belladonna of Sadness is the third in the trilogy, it’s the first of the three that Yamamoto created without Tezuka’s direct involvement.

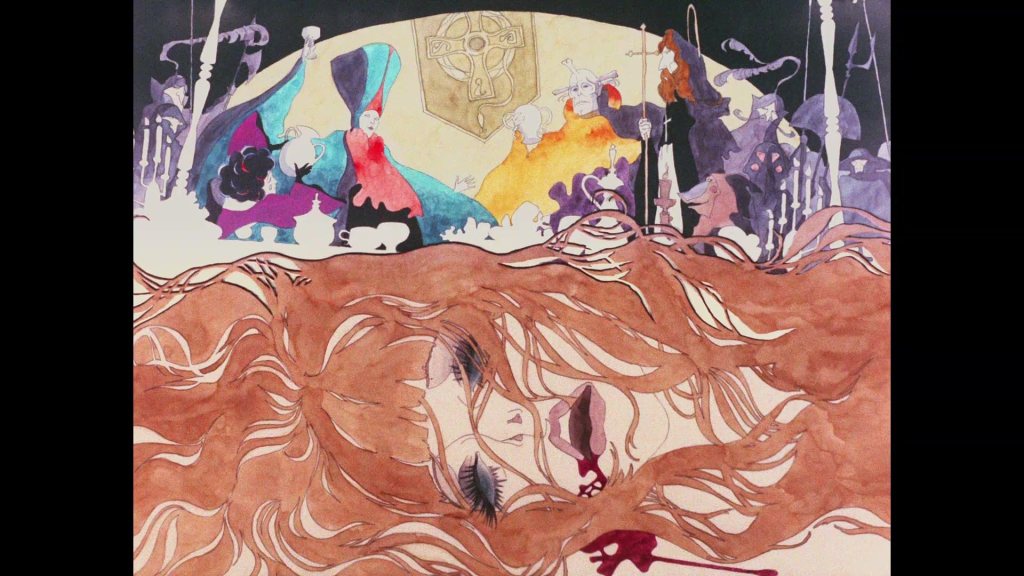

Belladonna of Sadness opens with a breathy opening theme composed by Masahiko Sato and performed by Mayumi Tachibana. Tachibana’s airy vocals communicate that this is an erotic film before a single character is introduced on screen, almost daring the audience to continue. The story begins long ago, with young couple Jeanne and Jean. The newlyweds make an offering to their king to christen their marriage, but the king finds their gift lacking. When Jeanne begs for mercy, and Jean explains that they are too poor to afford a nicer gift, the queen decrees that after the king has had a turn, everyone and everything should rape Jeanne. The court are depicted as ravenous demons and beasts, and the king thrusts aggressively into Jeanne as a crimson wound expands and contracts between her legs. The use of panoramic shots over painted images is particularly effective here; the scene isn’t particularly long, but it feels protracted by lingering shots. When Jeanne returns to Jean, he strangles her in anger, before fleeing in regret.

We watch Jeanne clean herself from the perspective of a mirror. We’re allowed to see her carnal pain directly, but in this private moment we’re forced to avert our eyes. A small phallic-looking spirit appears from her spinning wheel, who claims that he’s heard her call for help. He claims that Jeanne can make him grow, and become more powerful, and she asks for his help. In time, Jeanne becomes a successful seamstress, but a terrible disease starts to spread through the village. Jean becomes a tax collector, but when he isn’t able to extract enough money from the villagers, the king orders his hand cut off in punishment. As a result, Jean becomes a miserable drunkard. The spirit appears again, only larger this time, and he rapes Jeanne, claiming ownership of her body. However, Jeanne asserts that her soul still belongs to Jean, and to God. Jeanne becomes a powerful and respected moneylender in the village. The queen becomes jealous of the admiration the villagers have for Jeanne, so she declares her a witch, turning the village against her. When she runs home to hide from the mob, Jean refuses to open the door, and she is terribly beaten. Jean is a spineless piece of shit, by the way.

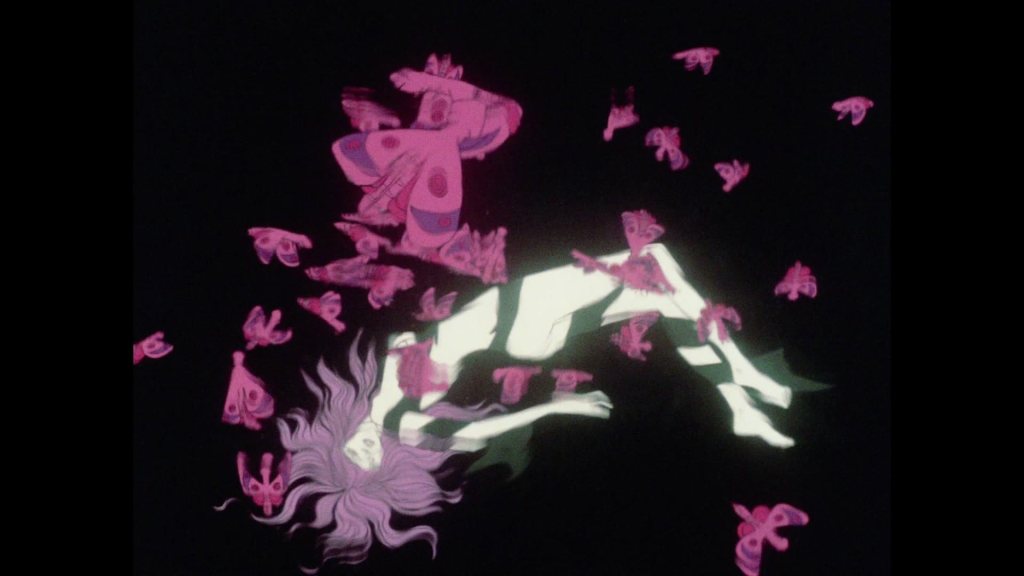

Jeanne is forced to hide in the woods, where the spirit appears to her again, even larger this time. Feeling totally abandoned, she makes a pact with the spirit, who reveals himself to be the Devil, submitting to wickedness completely. After an intimate fade to black, Jeanne awakens, and is surprised to find that, as the wife of the Devil, she is more beautiful than before and has been granted magic powers. She returns to the village and uses her power to create a cure for the disease, winning the favor of the public again. This sequence depicts Jeanne using sexuality as her magic, curing the peasantry with a town-wide, pox-ridden orgy. A page who previously attacked Jeanne, begs for her to help him seduce the queen. Love, it seems, is Jeanne’s power, and she creates a potion that causes the queen to fall for him. When the king finds the queen and page sleeping together, he orders their execution. Intimidated by her power, the king sends Jean to invite Jeanne to meet with him. He offers to elevate her status to the second highest seat in the land, but Jeanne refuses, saying she wishes to take over the entire world. At this, the king is outraged, and he orders for her to be burned at the stake. Jean is killed when he tries to fight back, and as Jeanne is burned, the faces of the villagers transform into Jeanne’s. Jeanne’s spirit goes on to ignite the flames of the French Revolution, centuries later.

I’ve glossed over some of the more graphic sexual content, but make no mistake, eroticism is on center display in this story. Reportedly, when pitching this film to his team Yamamoto said: “This is porn. It’s porn, but make it a pure love story.” The result is a psychedelic and overwhelming visual display. Especially to North American audiences, sexual content like this can be difficult to parse, but behind the nudity is a surprisingly feminist message. The story it tells is one of male gaze and female liberation: virginity and chastity are used to hurt and restrict Jeanne, but when she embraces her sexuality, it becomes a source of power for her. The orthodoxy that tells her her own sexuality is witchcraft is run by a man who becomes threatened when he sees a woman becoming more powerful than he is. Jeanne’s self discovery is cloaked in signals that we’re supposed to interpret as evil, but the Devil isn’t the villain of this story, the religious mythology is just a story told to keep women disempowered. When she wakes after becoming the Devil’s wife, Jeanne hasn’t become a hag or a succubus, she becomes a more beautiful version of herself, marking her transition from a demure virgin to a powerful sexual being; there is nothing unholy about her power, or the form she now takes. It’s by realizing this version of herself that she connects with the villagers, and inspires them beyond the limits of her mortality; when we see the villagers faces transforming into Jeanne’s, we understand that Jeanne’s will lives on through all the people she’s touched. Though her body perishes in the fire, the ideas that she inspired live on. That Jeanne isn’t portrayed as a slut for being sex positive is a remarkably progressive statement for the 1970’s. Perhaps that’s why, to Yamamoto’s surprise, the film was well received by female audiences of the time.

While watching this movie I was reminded of the still shots used in Ralph Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings (1978) and Wizards (1977), which also make use of still images and paintings in lieu of more traditional animation. Yamamoto was particularly inspired by the artwork of European tarot cards, which is maybe why so many beautiful watercolor paintings were used in the making of this film. The animation is so minimal here that characters don’t even have mouth flaps to distinguish who’s speaking, a cost-cutting measure that I think works in service of making the movie feel more dreamlike.

While I personally loved Belladonna of Sadness, I can’t recommend it for the faint of heart. Frankly, I was lucky that the people in our watch party weren’t more sensitive to the material, as seeing Jeanne be sexually violated could be overwhelming for some viewers. Most of the film’s runtime is graphic sexual content; the visceral imagery employed here is downright disturbing in some instances, and it can be difficult to recognize the difference between scenes of sexual assault and scenes of sexual empowerment. The limited animation, particularly the panoramic shots can make the story difficult to follow if the viewer isn’t paying attention, especially with how frequently the plot jumps forward in time. Belladonna of Sadness is a challenging movie that dares its audience not to look away from its unflinching visuals. To the impatient eye, it will come across as slow, confusing, and gratuitous; definitely prime your audience before showing it at your next watch party, as this film will not be up everyone’s alley.

For those who can tolerate the subject matter however, Belladonna of Sadness is a beautiful coda to an iconic era of Japanese animation, and I’d recommend it to anyone who cares deeply for the medium. The visuals are so trippy and gorgeous, I feel like I could take almost any random screenshot from this movie and hang it as art on my wall. It’s unfortunate, however, that this film plunged Mushi Productions into bankruptcy in 1973, a consequence of developing a film that was so un-commercial. The company was split up, and several employees went on to create studios of their own before the Mushi Productions reformed in 1977. Despite that, Belladonna of Sadness more than stands the test of time, and thanks to restoration efforts, is now more accessible than ever to challenge new audiences.