In college, a joke my friends and I often made about film studies is that if you wanted to sound smart, you talked about mise en scène; the joke being that no one knew what mise en scène meant, and that even the most sagely of professors would simply nod in agreement with whatever you were describing. This week, we took a look at a movie from the Cahiers du Cinéma top ten films of all time list, and a perfect subject for discussing this element of filmmaking: The Night of the Hunter (1955). This suspense thriller comes from Charles Laughton, more known for his acting career than his directing—The Night of the Hunter is his only directing credit. Did he nail it on the first try, or was the movie such a disaster he never tried again? Read on to find out!

The following contains spoilers for The Night of the Hunter (1955)

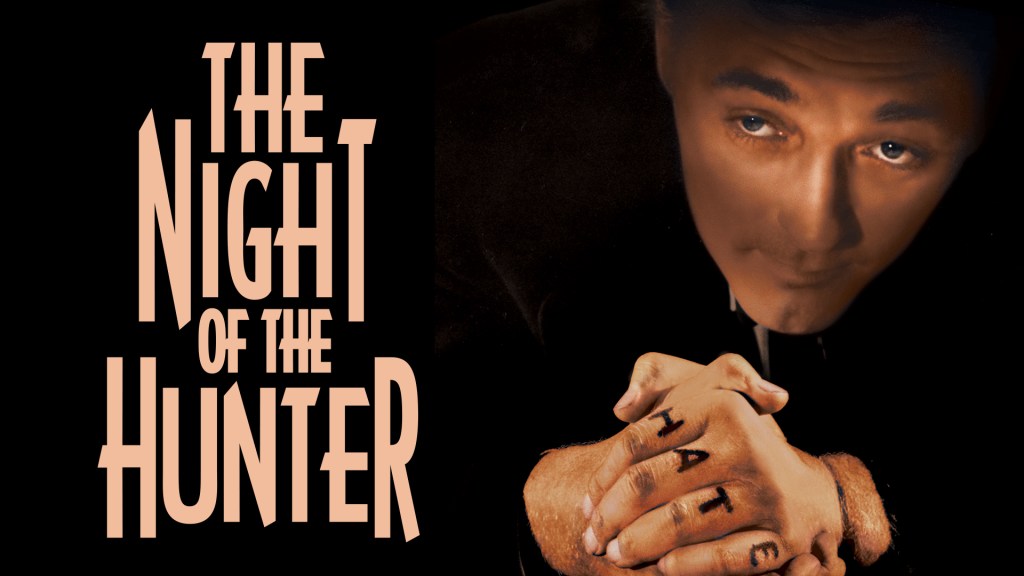

Serial killer and reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) is arrested, and sent to prison where he shares a cell with Ben Harper, a poor father of two who was arrested for killing two men in a bank robbery. Before he was caught, Harper ran to his house and hid the money, making his children, John and Pearl, promise to never reveal where the stash is. Powell attempts to get Harper to reveal the location under the guise of confession, but Harper dies with his secret, and upon being released, Powell makes his way to Harper’s hometown to find the fortune. Disguised as a preacher, Powell easily earns the unsuspecting people’s trust, and marries Ben’s widow. When he learns John and Pearl know where the money is, Powell sets his plot in motion to get the information, by any means necessary.

I could continue to break down the plot (as I’ve previously done… a trend I’m not sure will continue), but that’s not really why this movie is worth talking about. Powell’s relentless pursuit for the stolen money is captivating not only because of the depths he’s willing to sink to to get what he wants, but because of how well the actors portray their characters, and how beautifully so many of the shots are framed. Robert Mitchum plays his part perfectly, and his costuming contrasts him with everything else on the screen in almost every scene, his black outfit standing out even in the darkness of the basement scene. Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce are literal children in this movie, yet they have so much weight to carry, and they do. John is without a doubt the hero of the movie who resists Powell the most (no disrespect Pearl, you’re just five years old). The character goes through so much emotion over the course of the 92 minute runtime, and the kid just kills it. Child actors break so many movies, at no fault of their own, acting is hard, but I was just so impressed with these performances I had to mention them before diving into the cinematography.

Mise en scène is French for “setting the stage,” and refers to the all the elements that comprise a single shot. Stanley Cortez was the cinematographer on The Night of the Hunter, and a lot of the film’s quality can be attributed to his involvement. Cortez has a storied career as a cinematographer, and although this was Laughton’s first time in the chair, it was far from Cortez’s. The elements that a director utilizes in creating a shot include the sets, actors, props, costumes and lighting. In deciding the arrangement of those elements, directors can convey story and emotion through more artistic visuals. Put another way, mise en scène is simply how a shot looks. Powell’s outfit was eye catching from the start, albeit not very subtle, but it wasn’t until the scene in the bedroom with Willa that I couldn’t help but remark out loud how beautiful this movie is during our viewing.

The movie seems to go back and forth between beautiful full-sized sets that are shot almost like a stage play (lit incredibly) and an actual river in Moundsville, West Virginia. The sets are used brilliantly to show how small the characters are, and how trapped they feel being in a room with Powell. By showing us the frame of the rooms, the audience feels a sense of tension, maybe even claustrophobia. These moments are particularly memorable for the lighting, as dark shadows are cast over Mitchum, giving an almost art deco effect. The resulting shots are so artful, they more than stand the test of time, in part by taking advantage of being a black and white film. Later scenes with the children are filmed outside on an actual river, communicating how small they feel. Just breathtaking.

The contrast of light and darkness is maybe most explicit between Powell and Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), a widow who runs an orphanage that John and Pearl happen to run across. She stands opposite Powell as the statuesque force of good, appearing the antithesis to him in almost every way. Where he is a youthful, wicked man hunting them in a black hat, she is a wise, resilient woman providing safe harbor to them, in a white dress. Yet despite their differences, they reach an eerie harmony when singing their respective hymns, Cooper filling in the words that Powell omits, perhaps betraying his authenticity. It’s surprising that Rachel Cooper is such a strong independent woman, considering the time the film was made, but I was happy to see her, and her shotgun approach to dealing with Powell. She demonstrates her strength, handling the situation calmly, and without faltering, almost like a superhero who has arrived to protect the children.

When the police do come for Powell, John has a breakdown and runs towards him crying as the police arrest him, crying for the officers to not arrest his dad. This moment feels so raw, especially because we saw John paralyzed with fear in the mirroring scene at the beginning of the film. John beats his sister’s doll against Powell, and the stolen money explodes out of it, blowing into the wind; in the end, nobody got the money. John is also unable to testify against Powell because of his trauma, which ultimately leads to Powell getting a lighter sentence. The resolution of the story is also presented almost as a montage, expressing how much of a blur the events are to John.

The Night of the Hunter falls under the category of classic noir film; the movie explores the evil that lurks in Powell’s heart and contrasts it with the innocent, good-hearted children. An interesting way this was explored was through the Spoons, a couple of busybodies in the town who, in the first half of the movie, are wholesome and kind, taking in reverend Powell because of his connection to the church, but after he is revealed, become screeching malcontents angrily leading a mob under the guise of justice for the children. That the children run from the mob is evidence enough that this form of support is not helpful to the victims who have lost so much. I’m sure they appreciate that their tormentor gets captured, but clearly the events deal enough psychic damage to scar John for life.

Black and white movies aren’t for everyone, but this movie captivated me. The patience and skill it must have taken to get some of the pin-hole transitions and photogenic shots wasn’t obvious at first, but once I noticed it, I noticed it in almost every scene. The use of heavy shadows is in keeping with classic noir tradition, as are many of the film’s decisions around intimacy and violence, a product of the restrictions put on filmmakers at the time (pay attention during scenes in which Powell and Willa share a bed; couples had to keep at least one foot standing off of the bed, even during murder!) It’s no mystery to me why The Night of the Hunter makes the #2 spot on the Cahiers du Cinéma top ten films of all time; the movie demonstrates a care for the craft that modern movies struggle to achieve. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that Charles Laughton, upon completing his film, decided to retire from being a director, having mastered it on the first attempt. The Night of the Hunter is a wonderful reminder that every frame can be a painting.